The terms paradigm and theory are often used interchangeably in social science, although social scientists do not always agree whether these are identical or distinct concepts. This text makes a clear distinction between the two ideas because thinking about each concept as analytically distinct provides a useful framework for understanding the connections between research methods and social scientific ways of thinking.

For our purposes, we’ll define paradigm as a way of viewing the world (or “analytic lens” akin to a set of glasses) and a framework from which to understand the human experience (Kuhn, 1962). It can be difficult to fully grasp the idea of paradigmatic assumptions because we are very ingrained in our own, personal everyday way of thinking. For example, let’s look at people’s views on abortion. To some, abortion is a medical procedure that should be undertaken at the discretion of each individual woman. To others, abortion is murder and members of society should collectively have the right to decide when, if at all, abortion should be undertaken. Chances are, if you have an opinion about this topic, you are pretty certain about the veracity of your perspective. Then again, the person who sits next to you in class may have a very different opinion and yet be equally confident about the truth of their perspective. Who is correct?

You are each operating under a set of assumptions about the way the world does—or at least should—work. Perhaps your assumptions come from your political perspective, which helps shape your view on a variety of social issues, or perhaps your assumptions are based on what you learned from your parents or in church. In any case, there is a paradigm that shapes your stance on the issue. Those paradigms are a set of assumptions. Your classmate might assume that life begins at conception and the fetus’ life should be at the center of moral analysis. Conversely, you may assume that life begins when the fetus is viable outside the womb and that a mother’s choice is more important than a fetus’s life. There is no way to scientifically test when life begins, whose interests are more important, or the value of choice. They are merely philosophical assumptions or beliefs. Thus, a pro-life paradigm may rest in part on a belief in divine morality and fetal rights. A pro-choice paradigm may rest on a mother’s self-determination and a belief that the positive consequences of abortion outweigh the negative ones. These beliefs and assumptions influence how we think about any aspect of the issue.

In Chapter 1, we discussed the various ways that we know what we know. Paradigms are a way of framing what we know, what we can know, and how we can know it. In social science, there are several predominant paradigms, each with its own unique ontological and epistemological perspective. Recall that ontology is the study of what is real, and epistemology is the study of how we come to know what is real. Let’s look at four of the most common social scientific paradigms that might guide you as you begin to think about conducting research.

The first paradigm we’ll consider, called positivism, is the framework that likely comes to mind for many of you when you think of science. Positivism is guided by the principles of objectivity, knowability, and deductive logic. Deductive logic is discussed in more detail in next section of this chapter. The positivist framework operates from the assumption that society can and should be studied empirically and scientifically. Positivism also calls for a value-free science, one in which researchers aim to abandon their biases and values in a quest for objective, empirical, and knowable truth.

Another predominant paradigm in social work is social constructionism. Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman (1966) are credited by many for having developed this perspective in sociology. While positivists seek “the truth,” the social constructionist framework posits that “truth” varies. Truth is different based on who you ask, and people change their definitions of truth all the time based on their interactions with other people. This is because we, according to this paradigm, create reality ourselves (as opposed to it simply existing and us working to discover it) through our interactions and our interpretations of those interactions. Key to the social constructionist perspective is the idea that social context and interaction frame our realities.

Researchers operating within this framework take keen interest in how people come to socially agree, or disagree, about what is real and true. Consideration of how meanings of different hand gestures vary across different regions of the world aptly demonstrates that meanings are constructed socially and collectively. Think about what it means to you when you see a person raise their middle finger. In the United States, people probably understand that person isn’t very happy (nor is the person to whom the finger is being directed). In some societies, it is another gesture, such as the thumbs up gesture, that raises eyebrows. While the thumbs up gesture may have a particular meaning in North American culture, that meaning is not shared across cultures (Wong, 2007). So, what is the “truth” of the middle finger or thumbs up? It depends on what the person giving it intended, how the person receiving it interpreted it, and the social context in which the action occurred.

It would be a mistake to think of the social constructionist perspective as only individualistic. While individuals may construct their own realities, groups—from a small one such as a married couple to large ones such as nations—often agree on notions of what is true and what “is.” In other words, the meanings that we construct have power beyond the individual people who create them. Therefore, the ways that people and communities work to create and change such meanings is of as much interest to social constructionists as how they were created in the first place.

A third paradigm is the critical paradigm. At its core, the critical paradigm is focused on power, inequality, and social change. Although some rather diverse perspectives are included here, the critical paradigm, in general, includes ideas developed by early social theorists, such as Max Horkheimer (Calhoun, Gerteis, Moody, Pfaff, & Virk, 2007), and later works developed by feminist scholars, such as Nancy Fraser (1989). Unlike the positivist paradigm, the critical paradigm posits that social science can never be truly objective or value-free. Further, this paradigm operates from the perspective that scientific investigation should be conducted with the express goal of social change in mind. Researchers in the critical paradigm might start with the knowledge that systems are biased against, for example, women or ethnic minorities. Moreover, their research projects are designed not only to collect data, but also change the participants in the research as well as the systems being studied. The critical paradigm not only studies power imbalances but seeks to change those power imbalances.

Finally, postmodernism is a paradigm that challenges almost every way of knowing that many social scientists take for granted (Best & Kellner, 1991). While positivists claim that there is an objective, knowable truth, postmodernists would say that there is not. While social constructionists may argue that truth is in the eye of the beholder (or in the eye of the group that agrees on it), postmodernists may claim that we can never really know such truth because, in the studying and reporting of others’ truths, the researcher stamps their own truth on the investigation. Finally, while the critical paradigm may argue that power, inequality, and change shape reality and truth, a postmodernist may in turn ask whose power, whose inequality, whose change, whose reality, and whose truth. As you might imagine, the postmodernist paradigm poses quite a challenge for researchers. How do you study something that may or may not be real or that is only real in your current and unique experience of it? This fascinating question is worth pondering as you begin to think about conducting your own research. Part of the value of the postmodern paradigm is its emphasis on the limitations of human knowledge. Table 2.1 summarizes each of the paradigms discussed here.

| Paradigm | Emphasis | Assumption |

| Positivism | Objectivity, knowability, and deductive logic | Society can and should be studied empirically and scientifically. |

| Social Constructionism | Truth as varying, socially constructed, and ever-changing | Reality is created collectively. Social context and interaction frame our realities. |

| Critical | Power, inequality, and social change | Social science can never be truly value-free and should be conducted with the express goal of social change in mind. |

| Postmodernism | Inherent problems with previous paradigms. | Truth is always bound within historical and cultural context. There are no universally true explanations. |

Let’s work through an example. If we are examining a problem like substance abuse, what would a social scientific investigation look like in each paradigm? A positivist study may focus on precisely measuring substance abuse and finding out the key causes of substance abuse during adolescence. Forgoing the objectivity of precisely measuring substance abuse, social constructionist study might focus on how people who abuse substances understand their lives and relationships with various drugs of abuse. In so doing, it seeks out the subjective truth of each participant in the study. A study from the critical paradigm would investigate how people who have substance abuse problems are an oppressed group in society and seek to liberate them from external sources of oppression, like punitive drug laws, and internal sources of oppression, like internalized fear and shame. A postmodern study may involve one person’s self-reported journey into substance abuse and changes that occurred in their self-perception that accompanied their transition from recreational to problematic drug use. These examples should illustrate how one topic can be investigated across each paradigm.

Much like paradigms, theories provide a way of looking at the world and of understanding human interaction. Paradigms are grounded in big assumptions about the world—what is real, how do we create knowledge—whereas theories describe more specific phenomena. A common definition for theory in social work is “a systematic set of interrelated statements intended to explain some aspect of social life” (Rubin & Babbie, 2017, p. 615). At their core, theories can be used to provide explanations of any number or variety of phenomena. They help us answer the “why” questions we often have about the patterns we observe in social life. Theories also often help us answer our “how” questions. While paradigms may point us in a particular direction with respect to our “why” questions, theories more specifically map out the explanation, or the “how,” behind the “why.”

Introductory social work textbooks introduce students to the major theories in social work—conflict theory, symbolic interactionism, social exchange theory, and systems theory. As social workers study longer, they are introduced to more specific theories in their area of focus, as well as perspectives and models (e.g., the strengths perspective), which provide more practice-focused approaches to understanding social work.

As you may recall from a class on social work theory, systems theorists view all parts of society as interconnected and focus on the relationships, boundaries, and flows of energy between these systems and subsystems (Schriver, 2011). Conflict theorists are interested in questions of power and who wins and who loses based on the way that society is organized. Symbolic interactionists focus on how meaning is created and negotiated through meaningful (i.e., symbolic) interactions. Finally, social exchange theorists examine how human beings base their behavior on a rational calculation of rewards and costs.

Just as researchers might examine the same topic from different levels of inquiry or paradigms, they could also investigate the same topic from different theoretical perspectives. In this case, even their research questions could be the same, but the way they make sense of whatever phenomenon it is they are investigating will be shaped in large part by theory. Table 2.2 summarizes the major points of focus for four major theories and outlines how a researcher might approach the study of the same topic, in this case the study of substance abuse, from each of the perspectives.

| Theory | Focuses on | A study of substance abuse might examine |

| Systems | Interrelations between parts of society; how parts work together | How a lack of employment opportunities might impact rates of substance abuse in an area |

| Conflict | Who wins and who loses based on the way that society is organized | How the War on Drugs has impacted minority communities |

| Symbolic interactionism | How meaning is created and negotiated though interactions | How people’s self-definitions as “addicts” helps or hurts their ability to remain sober |

| Utility theory | How behavior is influenced by costs and rewards | Whether increased distribution of anti-overdose medications makes overdose more or less likely |

Within each area of specialization in social work, there are many other theories that aim to explain more specific types of interactions. For example, within the study of sexual harassment, different theories posit different explanations for why harassment occurs. One theory, first developed by criminologists, is called routine activities theory. It posits that sexual harassment is most likely to occur when a workplace lacks unified groups and when potentially vulnerable targets and motivated offenders are both present (DeCoster, Estes, & Mueller, 1999). Other theories of sexual harassment, called relational theories, suggest that a person’s relationships, such as their marriages or friendships, are the key to understanding why and how workplace sexual harassment occurs and how people will respond to it when it does occur (Morgan, 1999). Relational theories focus on the power that different social relationships provide (e.g., married people who have supportive partners at home might be more likely than those who lack support at home to report sexual harassment when it occurs). Finally, feminist theories of sexual harassment take a different stance. These theories posit that the way our current gender system is organized, where those who are the most masculine have the most power, best explains why and how workplace sexual harassment occurs (MacKinnon, 1979). As you might imagine, which theory a researcher applies to examine the topic of sexual harassment will shape the questions the researcher asks about harassment. It will also shape the explanations the researcher provides for why harassment occurs.

For an undergraduate student beginning their study of a new topic, it may be intimidating to learn that there are so many theories beyond what you’ve learned in your theory classes. What’s worse is that there is no central database of different theories on your topic. However, as you review the literature in your topic area, you will learn more about the theories that scientists have created to explain how your topic works in the real world. In addition to peer-reviewed journal articles, another good source of theories is a book about your topic. Books often contain works of theoretical and philosophical importance that are beyond the scope of an academic journal.

Theories, paradigms, levels of analysis, and the order in which one proceeds in the research process all play an important role in shaping what we ask about the social world, how we ask it, and in some cases, even what we are likely to find. A micro-level study of gangs will look much different than a macro-level study of gangs. In some cases, you could apply multiple levels of analysis to your investigation, but doing so isn’t always practical or feasible. Therefore, understanding the different levels of analysis and being aware of which level you happen to be employing is crucial. One’s theoretical perspective will also shape a study. In particular, the theory invoked will likely shape not only the way a question about a topic is asked but also which topic gets investigated in the first place. Further, if you find yourself especially committed to one theory over another, it may limit the kinds of questions you pose. As a result, you may miss other possible explanations.

The limitations of paradigms and theories do not mean that social science is fundamentally biased. At the same time, we can never claim to be entirely value free. Social constructionists and postmodernists might point out that bias is always a part of research to at least some degree. Our job as researchers is to recognize and address our biases as part of the research process, if an imperfect part. We all use our own approaches, be they theories, levels of analysis, or temporal processes, to frame and conduct our work. Understanding those frames and approaches is crucial not only for successfully embarking upon and completing any research-based investigation, but also for responsibly reading and understanding others’ work.

When Catherine LaBrenz, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Arlington’s School of Social Work was a child welfare practitioner, she noticed that several children who had reunified with their biological parents from the foster care system were re-entering care because of continued exposure to child maltreatment. As she observed the challenging behaviors these children often presented, she wondered how the agency might better support families to prevent children from re-entering foster care after permanence. In her doctoral studies, she used her practice experience to form a research project with the goal of better understanding how agencies could better support families post-reunification.

From a critical paradigm, Dr. LaBrenz approached this question with the understanding that families that come into contact with child welfare systems often experience disadvantage and are subjected to unequal power distributions when accessing services, going to court, and participating in case decision-making (LaBrenz & Fong, 2016). Furthermore, the goal of this research was to change some of the aspects of the child welfare system, particularly within the practitioner’s agency, to better support families.

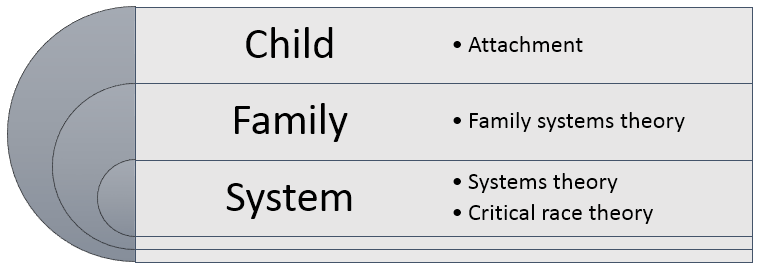

To better understand why some families may be more at-risk for multiple entries into foster care, Dr. LaBrenz began with an extensive literature review that identified diverse theories that explained factors at the child, family, and system- level that could impact post-permanence success. Figure 2.1 displays the micro-, meso-, and macro-level theories that she and her research team identified and decided to explore further.

At the child-level, Attachment theory posits that consistent, stable nurturing during infancy impacts children’s ability to form relationships with others throughout their life (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby, 1969). At the family-level, Family systems theory posits that family interactions impact functioning among all members of a family unit (Broderick 1971). At the macro-level, Critical race theory (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001) can help understand racial disparities in child welfare systems. Moreover, Systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1986) can help examine interactions among the micro-, meso- and macro-levels to assess diverse systems that impact families involved in child welfare services.

In the next step of the project, national datasets were used to examine child-, family-, and system- factors that impacted rates of successful reunification, or reunification with no future re-entries into foster care. Then, a systematic review of the literature was conducted to determine what evidence existed for interventions to increase rates of successful reunification. Finally, a different national dataset was used to examine how effective diverse interventions were for specific groups of families, such as those with infants and toddlers.

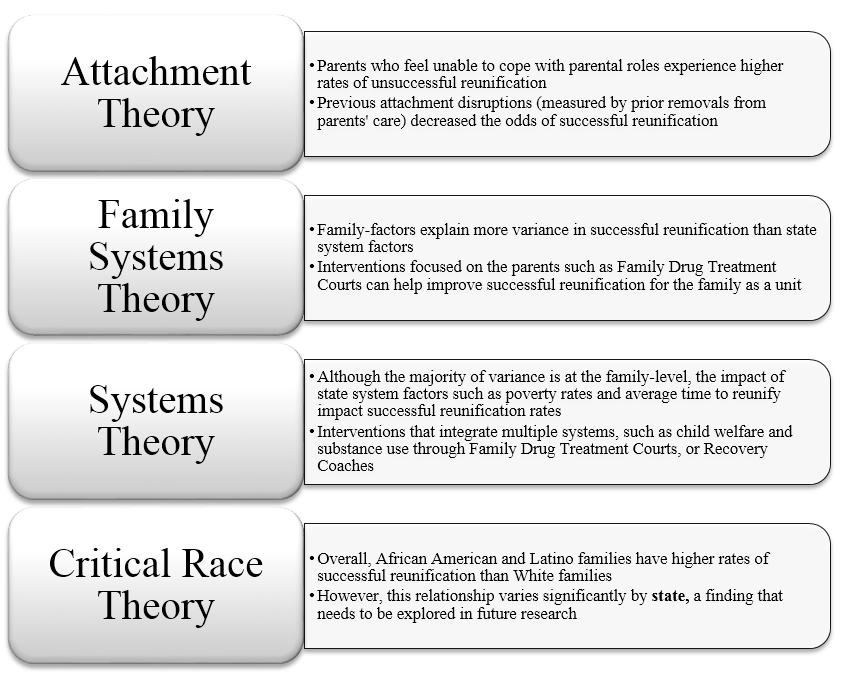

Figure 2.2 displays the principal findings from the research project and connects each main finding to one of the theoretical frameworks.

The first part of the research project found parents who felt unable to cope with their parental role, and families with previous attachment disruptions, to have higher rates of re-entry into foster care. This connects with Attachment theory, in that families with more instability and inconsistency in caregiving felt less able to fulfill their parental roles, which in turn led to further disruption in the child’s attachment.

With regards to family-level theories, Dr. LaBrenz found that family-level risk and protective factors were more predictive of re-entry to foster care than child- or agency-level factors. The systematic review also found that interventions that targeted parents, such as Family Drug Treatment Courts, led to better outcomes for children and families. This aligns with Family systems theory in that family-centered interventions and targeting the entire family leads to better family functioning and fewer re-entries into foster care.

In parallel, the systematic review concluded that interventions that integrated multiple systems, such as child welfare and substance use, increased the likelihood of successful reunification. This supports Systems theory, in that multiple systems can be engaged to provide ongoing support for families in child welfare systems (Trucco, 2012). Furthermore, the results from the analyses of the national datasets found that rates of re-entry into foster care for African American and Latino families varied significantly by state. Thus, racial and ethnic disparities remained in some, but not all, state child welfare systems.

Overall, the findings from the research project supported Attachment theory, Family systems theory, Systems theory, and Critical race theory as guiding explanations for why some children and families experience foster care re-entry while others do not. Dr. LaBrenz was able to present these findings and connect them to direct implications for practices and policies that could support attachment, multi-system collaborations, and family-centered practices.